After CRUD: Build and Consume an API

July 11, 2019

So at this point, you've picked a programming language, you've made your first projects, and you are starting to get the hang of things.

Awesome! Getting this far is a big accomplishment, and you should be very proud of that.

Now thinking ahead: outside of CRUD apps there are a few common topics that you will often encounter as you begin to build more complex apps and grow your skills as a developer.

Understanding the basics and having some experience with these topics will (like mentioned in my last post) show potential employers that you have a good foundation of knowledge and experience to build upon. Hiring you won't be a risky bet.

Learning these things will also allow you to break out of the mold of making simple CRUD apps and start making some fun and really useful things.

The first of these topics is APIs.

API

An API, or "application programming interface" is simply a way to request or submit data to and from a source. APIs are really the magic behind the internet today. They are what allow computers, devices, and servers to talk to each other.

The email app on your phone uses an API to retrieve your email from your email provider. The Twitter app uses the Twitter API to create tweets, retweets, and likes. If when you drive up to your house your air conditioning automatically turns on, that all happened by a series of devices communicating to each other via APIs.

APIs are basically a "contract" between two things—a way of describing how they are going to receive and exchange data. If you send data structured in a particular way to the Twitter API, it will create a tweet. If you request a particular URL from the Twitter API, it will return the data of all of your tweets.

As more apps and devices continue to talk to each other, APIs are becoming more and more commonplace—they're vital to understand.

Communicating on the web

In our modern life, we create standards—standards around electrical voltage, clothing sizes, languages, measurements, etc. Standards help us communicate better with each other. We know that if we communicate or build according to the standard we can expect anyone or anything else adhering to the standard to be able to understand and communicate back with us.

In the technology world, we use tons of standards for this very reason. It's why we can communicate so easily across the world using our internet-enabled devices. They're all talking to each other via layers upon layers of standards and protocols.

When it comes to the web, one of the foremost standards is the HTTP spec (yes the same spec used when you type http://google.com into your browser). There are many facets of the HTTP spec, but for now we're only concerned with a few parts: the URL, and the HTTP verb.

HTTP verbs

Similar to verbs in a spoken language, the HTTP verb is the action you want the API to take. It is also known as the request method, and it describes the intention of the request. Some of the most common HTTP verbs are: GET, POST, PUT/PATCH, and DELETE.

Hopefully the name of these verbs convey an idea of what they mean. A GET request is used when you want to, well, get or retrieve data. A POST request "posts" or sends data with the request—it usually means you want to create something new with the data you sent. For example, if you wanted to create a new tweet using the Twitter API, you would send a POST request.

A PUT or PATCH request is used when you want to update data, and DELETE obviously is used when you want to delete data.

The HTTP verb you send to an API partially determines what action the API will perform. We'll see these verbs in action in a minute, but the other factor is the URL you sent in the first place.

URL structure

Now here's where things start to deviate a little bit. Similar to our physical-world standards, not everyone agrees on what the best way to communicate is (i.e., metric vs English system). As a result of that, many different standards are born.

(There's a great XKCD comic about this.)

Here are some of the more popular API schemas:

- RESTful

- JSONAPI

- GraphQL

- SOAP

It's not important right now to know the intricacies of each of these. Just be aware that they exist and they all have their own different formats and ways of use. You will come across them at some point in your career.

Example: curling a Rails API

For most of my career I've been a Ruby programmer, and I love Rails. If you don't use Ruby or Rails that's totally fine—it's just an example API to play with. The concepts will transfer to any language or framework. This isn't about Rails at all; it's about the HTTP requests we'll be sending to the API.

The sample API I use in this post is pushed up here if you want to pull it down and try it yourself. It's also very easy to re-create if you already have Rails installed (see the README of the project).

There are many tools you can use to hit an API. There are desktop applications like Paw or Postman, and there are often language- or framework-specific tools built around a specific API (for example there's a ruby gem for the Twitter API), but what I'll be using here is something that comes already installed on Macs called curl.

Curl is a very useful tool, and it will help us demonstrate these basic API concepts. Curl is a command line tool, and so you can use it in your terminal by just typing the word curl and then the arguments you want to pass to it.

Let's jump right into an example:

(Note: usually a $ in front of something in a code example means run this at the command line.)

All users

$ curl http://localhost:3000/users

[

{

"id": 1,

"name": "Bob",

"age": 50,

"created_at": "2019-07-10T19:42:40.002Z",

"updated_at": "2019-07-10T19:42:40.002Z"

},

{

"id": 2,

"name": "Susy",

"age": 25,

"created_at": "2019-07-10T19:42:44.766Z",

"updated_at": "2019-07-10T19:42:44.766Z"

}

]

Rails follows the RESTful API convention. In a RESTful API, the HTTP verb and the URL structure are very specific.

In this example, we sent a GET request (that's the default for curl), and we requested the /users resources. By REST convention, a plural resource name with a GET verb means return all of the resources for that type (in this case, User).

I had already added some users into the database, and so we see those two users' data returned.

Retrieving a specific user

If we wanted to retrieve a specific user, based on REST convention we would augment our URL and add an ID (identifier). From the result of our first API call we can see Bob's ID, which is 1. So, we add that ID to our URL to get Bob's specific resource (aka user):

$ curl http://localhost:3000/users/1

{

"id": 1,

"name": "Bob",

"age": 50,

"created_at": "2019-07-10T19:42:40.002Z",

"updated_at": "2019-07-10T19:42:40.002Z"

}

Creating a user

To add a new user, we need to change up our request a bit. First, since we're now adding new data we need to use a POST request. Also, we obviously need to send the data for the user we want to make. Again the format of all of this is specific to the API schema you're following, but here's what it looks like for a RESTful API:

(The \ at the end of the line just lets me break it into multiple lines for readability—you can do it all as one line if you want.)

$ curl -X POST http://localhost:3000/users \

-d '{ "user": { "name": "Bret", "age": 18 } }' \

-H "Content-Type: application/json"

{

"id": 3,

"name": "Bret",

"age": 18,

"created_at": "2019-07-10T20:11:13.283Z",

"updated_at": "2019-07-10T20:11:13.283Z"

}

And our new user is made! A few things changed there, so let's go piece by piece:

curl -X POST

The -X flag is shorthand for passing --request, which allows us to tell curl which HTTP verb to use. By default it's GET, but for creating data we send POST.

Next, the actual data we're sending:

-d '{ "user": { "name": "Bret", "age": 18 } }'

As you can see, it looks a lot like how a user would be represented in data-form. This data is in the JSON format, so the last thing we need to tell the API is the format of the data we're sending it—so it knows how to parse and deal with it:

-H "Content-Type: application/json"

Here we're using a new flag as well, -H or --header. This represents an HTTP header. HTTP headers are extra information we pass along with the request—meta information.

The header is Content-Type, aka, this is the type or format of the content I am sending you. In this case, it's JSON, or in HTTP-speak: application/json.

HTTP headers are very important and used in nearly every API. They can pass things like the content type (as above), a special token to prove who you are or authenticate as a user, and more. You will become very familiar with them over time.

Updating a user

Updating data is pretty similar to creating it. We're performing a different type of action (updating instead of creating), so we need a new HTTP verb: PUT (there's also PATCH which is similar but has its own differences).

And, since we're acting on a specific resource, we'll go back to using its ID to target it specifically:

$ curl -X PUT http://localhost:3000/users/3 \

-d '{ "user": { "age": 20 } }' \

-H "Content-Type: application/json"

{

"id": 3,

"age": 20,

"name": "Bret",

"created_at": "2019-07-10T20:11:13.283Z",

"updated_at": "2019-07-10T20:20:40.400Z"

}

Pretty straightforward right?

PUTfor the verb/users/3for that specific user'{ "user": { "age": 20 } }'the data we want to update (age)application/jsonthe same content type

Deleting a user

And finally, deleting a user. By now you could probably guess what the request should look like:

curl -X DELETE http://localhost:3000/users/3

Easy-peezy. Just change the HTTP verb to DELETE, and again target that specific user: /users/3.

A scary chart

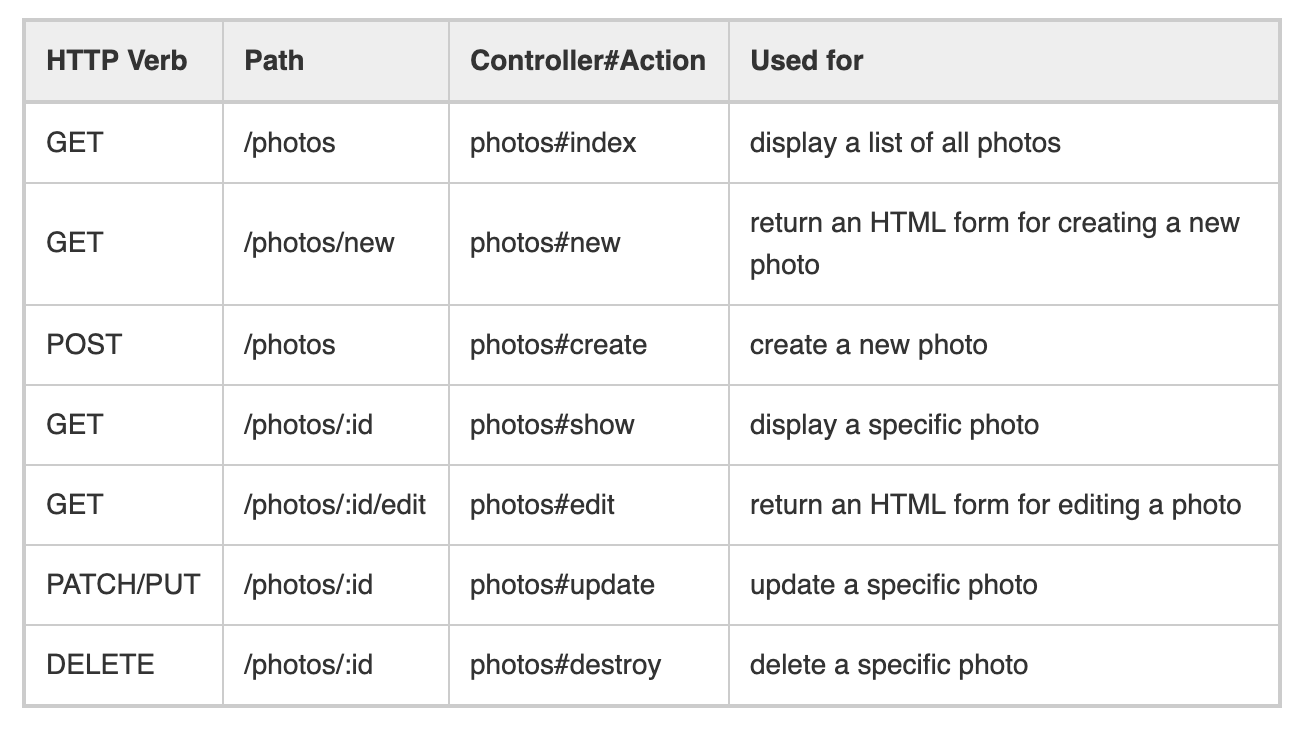

Now that we've worked through those examples, I can show you this scary RESTful-routing chart. This chart is from the Rails routing guide, and it describes the RESTful routing for a photo resource (we used user in our example, but it works the same way).

If you look at this chart, you'll find that the pattern we used for our API is exactly the same as this chart—it is still using REST after all. There's a couple new ones that don't make sense outside of a CRUD-app context (you don't need a new or edit route for an API), but you should see the similarities between this chart and our API requests.

Now go get some practice

APIs are a large topic—and this was obviously far from exhaustive—but after you work through some examples like these you'll find that APIs are really not that scary at all. No matter how complex they seem, they're just making requests to routes with a specific verb, URL, data, and headers.

As you start building more complex applications, they will begin communicating with other apps via APIs. This is really where the true power of the internet comes in—and it gets really fun!

So, go get some practice building and using an API. It will be a very useful skill. Here's some ideas for you:

- What are the most common HTTP response codes and what do they represent? (You probably already know "404 not found.")

- What are the most common HTTP verbs sent with a HTTP request, and what CRUD actions do they map to?

- Build a simple user CRUD API like the one above

- Give each user an authentication token (a random string) and pass this as a header to authenticate them. Only allow a user to update their own information.

That's all for this one. Feel free to reach out to me on twitter (@johnmosesman) if you have any questions on this or any other development topic.

John